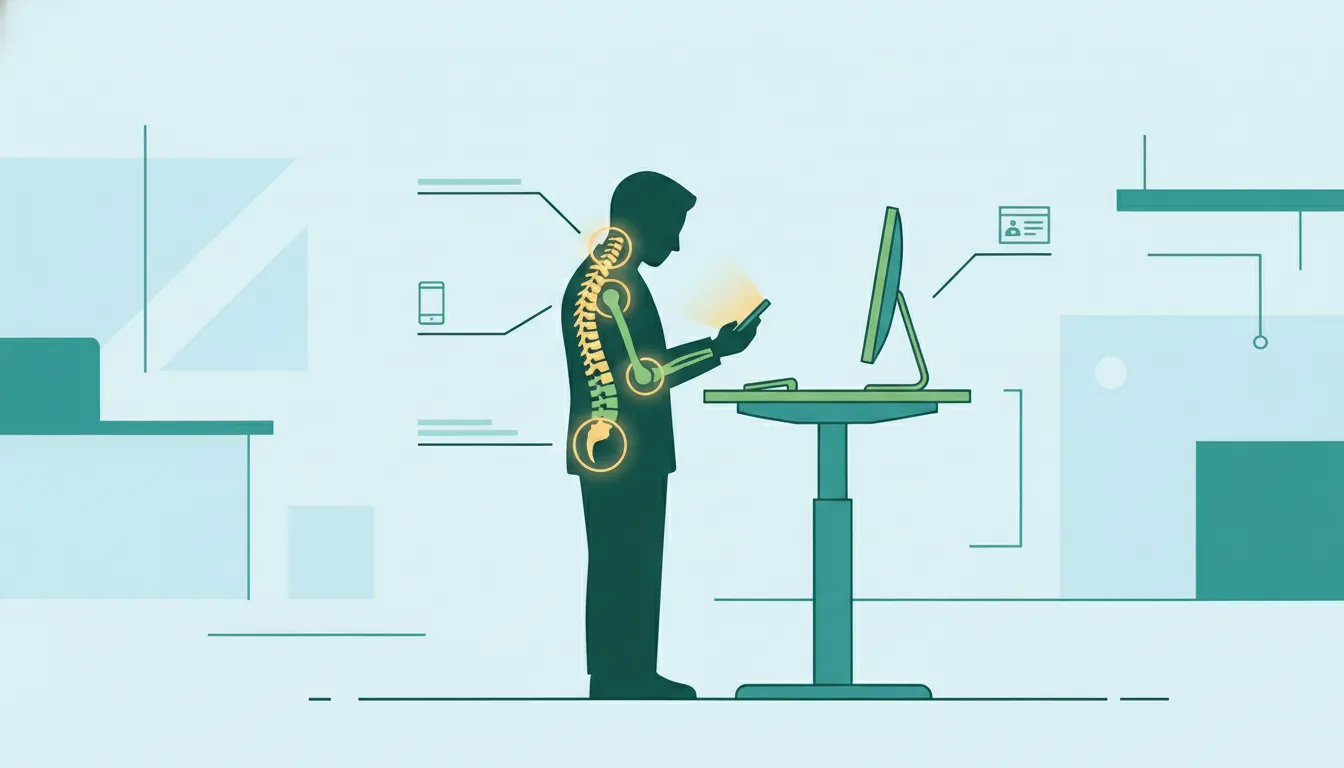

The human body is an architectural masterpiece of evolution, designed for movement, endurance, and adaptability. However, the rapid acceleration of the digital age has outpaced the slow crawl of biological evolution, placing our musculoskeletal systems in a precarious position. For decades, the primary concern of occupational health was the “sedentary epidemic.” We were warned that “sitting is the new smoking,” a mantra that led to a global revolution in office design. The result was the rise of the standing desk and the glorification of the upright worker. Yet, as we traded our ergonomic chairs for standing mats, we simultaneously tethered ourselves to handheld devices. This combination—prolonged static standing coupled with the constant use of smartphones and tablets—has birthed a specific cluster of musculoskeletal issues that clinicians are beginning to recognize as a “new” arthropathy of the modern era.

To understand this shift, one must first look at the biomechanics of standing. While standing is inherently more active than sitting, the “standing work” trend often ignores the distinction between dynamic movement and static loading. When a person stands in a fixed position for hours, the heart must work harder to pump blood against gravity from the lower extremities. Simultaneously, the joints of the knees, hips, and lower back are subjected to continuous hydrostatic pressure. When we add the “gadget factor” to this equation, the physical toll changes character. The head tilts forward to glance at a screen, shifting the center of gravity and forcing the muscles of the neck and upper back to compensate for a weight that effectively triples as the angle of the neck increases.

The Mechanical Toll of the Upright Tether

The term arthropathy generally refers to any disease of the joints. Traditional arthropathies are often linked to aging, autoimmune responses, or acute injury. The modern variation, however, is a repetitive strain phenomenon that manifests as chronic inflammation and premature wear. When an individual stands at a workstation while looking down at a mobile device, they create a “closed kinetic chain” of stress. The tension begins in the cervical spine—often called “text neck”—and travels down the kinetic chain. Because the person is standing, the lower back cannot redistribute this weight as it might when seated; instead, the lumbar spine must stabilize the entire shifting mass, leading to a flattening of the natural curve and increased pressure on the intervertebral discs.

Furthermore, the hands and wrists are rarely spared. The ergonomics of holding a smartphone while standing are significantly different from using a keyboard on a desk. In a standing position, the arms often hang unsupported, putting the weight of the device entirely on the small muscles of the thumb and the tendons of the wrist. This has led to an uptick in “smartphone thumb” (De Quervain’s tenosynovitis) and various forms of tendonitis that are exacerbated by the lack of forearm support common in standing environments. Unlike the coordinated movements of walking, which act as a pump for joint fluid and blood circulation, static standing causes joint fluid to settle, leading to stiffness and a higher concentration of inflammatory markers in the synovial fluid.

The Vascular Connection and Joint Health

One of the most overlooked aspects of this new lifestyle-induced arthropathy is the relationship between vascular health and joint integrity. Static standing is a well-known risk factor for chronic venous insufficiency. When blood pools in the lower legs due to gravity and inactivity, it creates an environment of localized edema. This swelling does not just affect the veins; it puts pressure on the surrounding tissues and the joint capsules of the ankles and knees. Chronic swelling can lead to a low-grade inflammatory state in the joints, mimicking the early stages of osteoarthritis.

The introduction of gadgets into this scenario acts as a distractor that prevents the body’s natural “micro-movement” signals. Normally, a person standing still would shift their weight instinctively every few minutes. However, the cognitive load of interacting with a digital interface—be it an email, a social media feed, or a work application—often overrides these subtle biological prompts. We become “frozen” in a state of digital absorption. This prolonged immobility in an upright position starves the cartilage of the nutrients it usually receives through the “sponge effect” of movement, where compression and release cycle joint fluid. Without this cycle, the cartilage becomes brittle and more susceptible to micro-fractures.

Redefining Ergonomics for the Hybrid World

The journalistic narrative surrounding workplace health is shifting from a simple “sit less” message to a more nuanced “move more” philosophy. Experts are beginning to realize that the standing desk is not a panacea, especially when used in conjunction with mobile technology. The “new” arthropathy requires a new set of solutions that move beyond furniture. It involves a fundamental change in how we perceive our relationship with our devices. If the standing desk was the hardware update of the 2010s, “dynamic positioning” is the software update required for the 2020s.

Mitigating the risks of this modern arthropathy involves breaking the static cycle. Medical professionals now suggest the “20-8-2” rule: for every half-hour of work, sit for 20 minutes, stand for 8 minutes, and move or stretch for at least 2 minutes. When gadgets are involved, the height of the device is more critical than the position of the legs. Bringing the device to eye level, rather than dropping the head to the device, can prevent the cascading postural failures that lead to joint pain. Additionally, the use of compression therapy and anti-fatigue mats has become a standard recommendation for those whose professions mandate standing, yet these are merely bandages on a larger problem of technological over-dependence and physical stagnation.

The Long-term Prognosis

If we do not address the rise of this modern arthropathy, healthcare systems may face a wave of “early-onset” joint degeneration in the coming decades. We are seeing thirty-year-olds with the cervical spine profiles of sixty-year-olds and retail workers with chronic knee inflammation that was once reserved for heavy laborers. The digital lifestyle is not going away; if anything, our reliance on handheld interfaces will only deepen with the integration of augmented reality and more immersive mobile tools.

Ultimately, the goal is not to abandon technology or return to a purely sedentary office life, but to foster a culture of biological awareness. The human body is a dynamic system that thrives on variety. By recognizing that standing while staring at a screen is a specific, high-stress physical activity, we can begin to implement the necessary offsets. The “new” arthropathy is a signal from our bodies that we have pushed the limits of static endurance. Listening to that signal requires a blend of ergonomic discipline, technological restraint, and a return to the movement-based roots of our species.

Sources and References

- Journal of Physical Therapy Science: The effect of smartphone usage time on posture and respiratory function

- Surgical Technology International: Assessment of stresses in the cervical spine caused by posture and position of the head

- American Journal of Epidemiology: Relationship between occupational standing and sitting and incident heart disease

- Applied Ergonomics: The effects of a sedentary versus active upright workstation posture